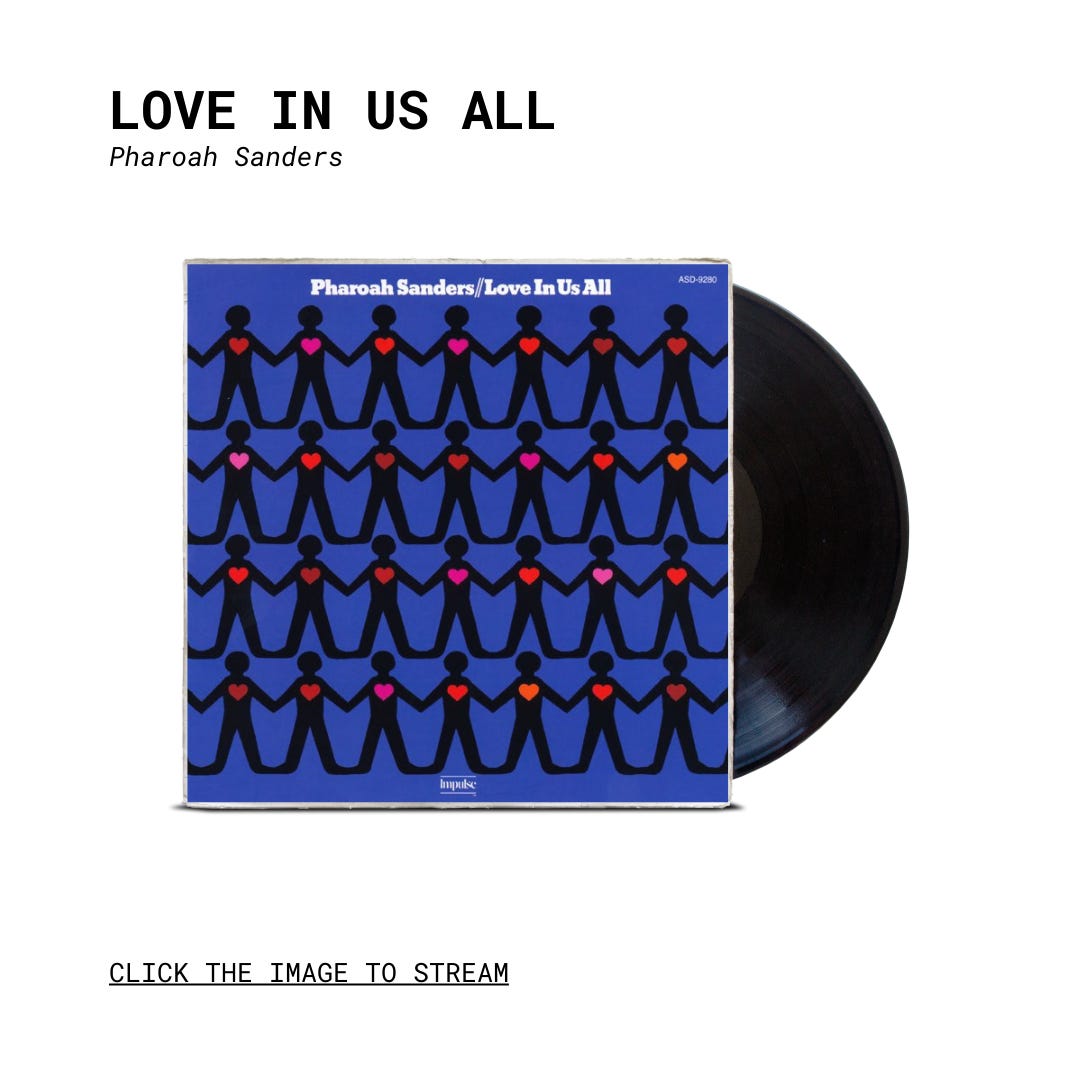

“Love in Us All” by Pharoah Sanders

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of my favorite Pharoah Sanders free jazz album.

Hello! 😊👋

Welcome to a new edition of the Best Music of All Time newsletter!

Today’s music pick marks this month’s 50th anniversary of my favorite record from free jazz legend Pharoah Sanders.

Genre: Free Jazz, Experimental

Label: Impulse!

Release Date: January 1, 1974

Vibe: 🥲

To describe Pharoah Sanders’ work on Love in Us All simply as “free jazz” or “cosmic jazz” is to undersell how captivating it is emotionally. Most jazz fans associated those two subgenres with dense, complex compositions that require an almost academic attention to detail to fully “understand.” The granddaddy of all free jazz behemoths is John Coltrane’s 1966 album Ascension, which features Sanders in a key role on tenor saxophone. The completely improvised recordings are full of dissonant intensity, building on previous contributions from legends like Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman. But, in terms of setting the stage for the next half-century of jazz experimentation, you could argue none of that happens without Ascension or, in its immediate aftermath, Sanders in particular.

Beginning in 1969 with Karma, Pharoah Sanders asserted himself as a prolific, pioneering figure in the free jazz movement. His multiphonic techniques fueled an approach to harmony and energy that’s hard to encapsulate in a single term. His playing, once described by Coleman as the best in the world, is thoughtful and brooding, often taking its time to build to grandiose, ethereal statements. During the next five years, he releases a half-dozen classics on Impulse!, including Jewels of Thought, Black Unity, and Wisdom Through Music. Those four records are excellent and merit a spot in any audiophile’s collection, as does his incredible 2021 collaboration with Floating Points, Promises. But, as good as they are, none of them have burrowed their way into my soul quite like Love in Us All.

A lot of that has to do with the first of two compositions, wonderfully titled “Love is Everywhere.” Spaning 20 minutes, the track is chaotically rhythmic, built around euphoric peaks and pristine valleys. After a headrush of an opening five minutes, the pace slows down, giving pianist Joe Bonner plenty of room for some gorgeous improvisation on the keys. The percussionists, including Lawrence Killian, Badal Roy, and James Mtume, punctuate his runs by layering the groove piece by piece. By the time Sanders’ saxophone pops back up in the mix, you’re totally immersed in the positive, affirming energy that radiates through your headphones or speakers. It’s one of the most enveloping pieces of music I’ve ever heard.

One of the thrills of listening to Sanders is how he wears his emotions on his sleeve when he plays. Especially as he became a more seasoned and adventurous sonic experimentator, you got the sense that he was acting purely on instinct, without feeling any need to bury subtext or deeper academic meeting in his music. “I don’t like to talk about what my playing is about. I just like to let it be,” Sanders explained in 1968. “If I had to say something, I would say it was about me. About what is. Or about a Supreme Being. I think I am just beginning to find out about such things, so I am not going to try to force my findings on anybody else. I am still learning how to play and trying to find out a lot of things about myself so I can bring them out.”

That emotional directness is even more apparent on “To John,” the record’s second and final track on the album. The musicians dip, dodge, and jab around each other’s playing, swelling like dark clouds over a calm body of water. Sanders’ creative tonal shifts are nothing short of remarkable, bending the saxophone’s sound to his will. At times, the instrument emits shrieks with fright. Other times, it sounds like it’s crying tears of joy. His solos cut through a thicket of clashing ideas, building to a moment that I won’t describe in detail, but, in keeping with the coming storm metaphor, is the band’s version of darkness parting to emit light and display a freshly-minted rainbow. As they settle into a tight groove and barrel towards the record’s finish, it leaves as pure a sense of wonder as you’ll experience listening to free jazz.

In a way, Love in Us All is an example of how streaming can help us preserve and catalog crucial records from music’s history, especially when physical copies have long since gone out of print and past editions are hard to find. I was lucky to come by a CD copy of this album while in Tokyo, a city that’s still so infatuated with physical media, your average record store has three or four floors of floor-to-ceiling shelves busting with incredible gems from the past. But not everyone has that luxury—financially, temporally, or otherwise—which means streaming providers are the great equalizer for catalogs like the one Pharoah Sanders left behind. He played well into his 80s and gifted us with some of jazz’s most captivating creations. To miss out on its glory because of a lack of access would be a shame.

To capture his essence as a musician and band leader, I’ll leave you with this quote from that same 1968 interview:

“When I play, I try to adjust myself to the group, and I don’t think much about whether the music is conventional or not,” “If the others go ‘outside,’ play ‘free,’ I go out there too. If I tried to play too differently from the rest of the group, it seems to me I would be taking the other musicians’ energy away from them. I still want to play my own way. But I wouldn’t want to play with anybody that I couldn’t please with the way I play.”

👉 Don’t forget to click the album image to stream the album on your favorite platform 👈

Speaking of Coltrane’s ASCENSION, get the CD The Major Works of John Coltrane because it has both takes 1 & 2, recorded at the Van Gelder studio June 28, 1965.

'Karma' is a good example where the physical LP awkwardly breaks the flow of a long jazz number (as on "The Creator Has A Master Plan," which is divided over both sides). I've had my LP for decades and had never heard the unbroken flow of the entire song until streaming/Spotify! I don't have a problem with the interrupted flow of the LP, as it's what I have always known, but it was a revelation hearing the full 33 minutes in one sitting!